This summer I read Richard P.Feynman’s ‘Six Easy Pieces: Essentials of Physics Explained by Its Most Brilliant Teacher’

I packed for the Swedish lakes not because of a new found interest in Physics, but because I wanted to see well a complex issue can be communicated in the hands of a master craftsman.

I was not disappointed. Physics seemed useful and interesting in ways that school never managed.

You can get an impression of how well he conveys knowledge in this lecture clip.

Feynman communicates so well for three reasons.

First, he put a lot of thought and work into preparing these introductory lectures.

Second, he was always trying to improve his lectures, and even when the talks had become sold out, he was never happy with them. He was always improving them.

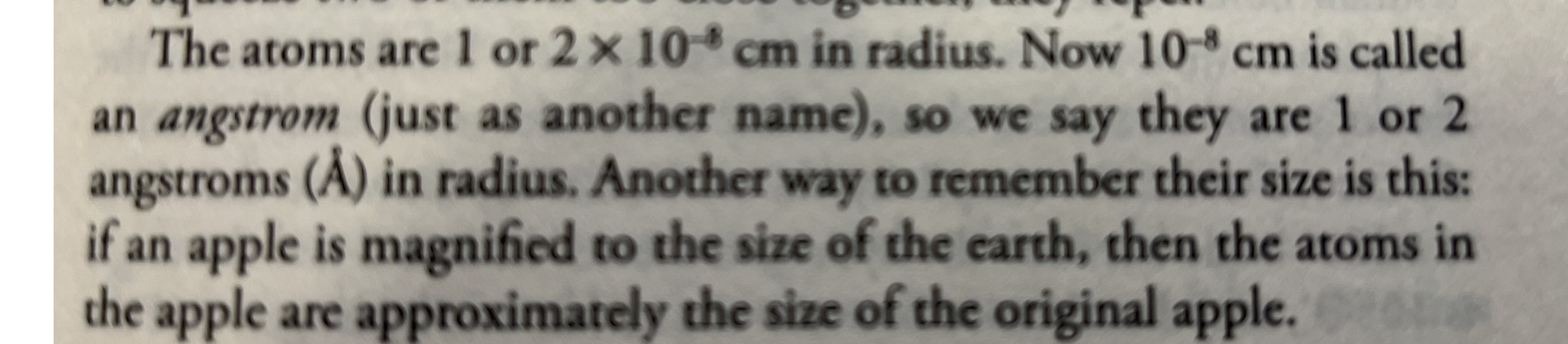

Third, he uses a simple device to communicate complexity. He uses analogy and metarphors alot. Below is an example:

p.5, Six Easy Pieces

Fourth, he uses a plan, or a map, to take the audience through a journey of understanding.

Fifth, he uses plain and simple words.

What Can Public Policy Writing Co-opt

I realised, whilst reading Feynman, that most public policy writing lacks some simple devices that have been used for a few thousand years to help the reader and listener understand. It is the use of analogy, metaphors, and parables.

It is like this device is alien to Brussels. It can’t be. Many of us in Europe were brought up on a diet of children’s stories that were rich in fables teaching useful life lessons in entertaining stories – the king who had no clothes, the boy who called wolf. These two stories should be essential reference texts for anyone working in public policy.

Those of us who benefited from a religious education, mine with the De La Salle Brothers, benefited from parabolic teaching, i.e. learning from parables.

Why good is harder than bad

Good public policy writing is not easy to pull off. It is a lot easier to write something long and unreadable.

There are three things you need to have in place before you sit down to write:

- You want to communicate your ideas to the reader.

- You know your issue well.

- You know how to communicate in writing, and if meeting people, communicate when speaking.

It is a combination that few seem to have, especially 1.

These mental constructs are embedded in our minds but rarely used in public policy writing. Most position papers resemble dry verbiage that’s fallen off a lectern at a doctoral symposium. I would have used the term data dumps, but there are too few data dumps in most position papers in Brussels. . They are often written for a clique of fellow travellers rather than the informed mainstream. They tend to be used as a device to secure internal agreement on an issue rather than as a means of outward persuasion.

If you can convey your public policy position with the clarity and passion of Richard Feynman, you’ll persuade many.