On 30 March 2002, the European Commission published their proposal for ‘Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation‘.

All going to plan, the Commission will have adopted one of the most radical pieces of environmental product regulation without many people noticing. I’d estimate this will be agreed to by the end of 2023.

I have a particular interest in environmental product regulation, having worked on it, on and off, for over 20 years. Some of my more obscure academic publications now have a longer shelf life. Indeed, the issues that come up on this file give me a flashback to my time in DG ENV working on WEEE and ROHS back in the early 2000s.

Why is it radical

The scope of the issues the law will look at a broad range of issues, including durability, reliability, reusability, upgradability, presence of substances of concern, energy efficiency, resource efficiency, remanufacturing and recycling, environmental impacts, including carbon and environmental footprint, and the expected generation of waste materials.

This is a lot of information that companies making products (and their suppliers) are, sooner rather than later, going to need to get hold of and hand in.

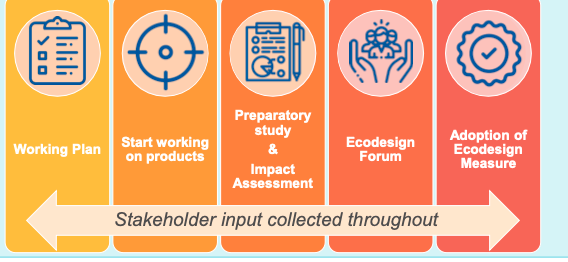

The legislative proposal won’t set measures. You’ll have to wait for the real measures to come later on through a mix of delegated acts and implementing acts. The likely measures will be flagged well in advance and have a lot of chances to participate.

The Process for new Measures

The process is familiar to anyone whose worked on the current ecodesign directive.

The challenge is that once your product is added to the working plan, you’ll have to bring a lot of data and information to the table to get it removed.

There will be some new information requirements including a Digital Product Passport.

What’s interesting about the proposal is that it gives a lot of flexibility to the regulator to introduce new product-specific rules or complement existing rules. For example, complimentary rules on construction, products, packaging and chemicals are anticipated.

For chemicals, an area that I work on a lot, this would include information requirements for the tracking of substances of concern; details in the digital product passport; and delegated acts for substances of concern that, for example, would negatively affect re-use or recycling, and as such be banned.

The challenge is that many important elements will go through the delegated act produce which means it is hard to block what the Commission put forward. You will need 20 Member States or 353 MEPs to veto a measure at the security stage.

How this Can Impact You

Pratically, this will mean for many companies that they will need to keep a very close eye on their usual product regulation (packaging, electronics, chemicals etc.).

Keeping up to date on the the issues coming onto the work plan and going through the sustainable products regulatory machine. As soon as that happens, a lot of information, from the producers and their suppliers will need to be brought to the table. Silence is not an option.

This will mean many companies will have to keep their ears to the ground and engaged with the lead officials and members of the eco-design forum (experts and experts from the member states).

Market Opportunities

Companies who are front runners could easily use this process to get their competitors taken out of the market. The original ethos of this front-runner legislation is to set mandates that forces all companies to meet the top runner’s standards. Those that can’t, leave the market, and every few years, the standards are revised upwards again to force a process of continued improvement.

I’ve seen this used many times. It is something well received by Commission and Member State regulators, and as soon as it ticks the boxes of what they need, they’ll be more than happy to put it through the regulatory machine.