I am often asked how to deal with policymakers.

The advice below is based on working for NGOs, industry, politicians and the Commission. It’s the same advice I give friends working for industry and NGOs

Some people apparently liken the prospect of dealing with a policy maker as they would meeting ET.

Many people react like Michael and Gertie when they met ET.

It’s important to get it right. If you get it wrong, you’ll set back your cause, sometimes irreversibly.

I may have an advantage. I’ve been an official and worked for politicians. We must have the same DNA.

It’s key to understand who you are dealing with. On any given issue there are going to be no more than a handful – around 20 – who really decide.

They likely know each other well. Many will have worked together at some time in their career. Some will be friends. The decision-making chain is shallow.

From this flows the obvious. Don’t moan and complain about any official personally. It’s going to be counterproductive. It’s such a small world that it will not look good on you.

Too often, when people lobby they speak a language that officials and politicians cannot understand. It often sounds as if they are speaking the language from the Phaistos Disc.

There is an easy way to tell if you have lost your audience. They stop listening to you. Your audience will start chatting amongst themselves, laugh in disdain at your points, and cross their arms in front of you.

If you lose your audience, there are two things you can do. First, re-calibrate on the spot, and speak to them in a way that they understand. Second, if that does not work, end the meeting abruptly, and leave.

If you can’t speak to them in a way your audience can understand, you should not be in the room.

When working for Anita Pollack MEP, an industry delegation came in and gave a master class in male chauvinism that would not have been out of place before women got the right to vote.

When working for WWF on fisheries, the head of Cabinet called me in to meet, as he, at last, understood what we were asking for. The reason for this change? I had banned the use of fishing quota equations in letters. Once translated into plain English, he understood what we asking for.

The only time I bring a lawyer to the meeting is if the meeting is with a lawyer. Otherwise, I use their advice and leave them outside. I do so for a very simple reason. It is seen by most, if not all, officials I know that your scientific or technical case has no merits, and you are getting ready to go to Court. That’s not a good signal to send.

If the meeting is about a legal point, bring them in, and ask for the other side’s lawyer to be there. Ideally, send a summary of the legal argumentation in advance. As you are paying by 6-minute increments, you don’t want to run up needless billable hours on a point that can be disposed of in minutes.

Today, I have switched from one seemingly technical and science heavy areas, fisheries, to another, chemicals. The lessons remain the same.

It’s a key cornerstone of both, that you need to keep up to date, and have a flow of word class and up to date data and studies. You need them to objectively and dispassionately deal with each and every point that can be raised.

This is just a baseline expense that needs to be borne. There is no shying away from it. As the body of knowledge increases, you need to be on top of those changes, and commission new studies to answer any questions that come up.

You need to do this because governments, international organisations, and universities, will be working to find answers to emerging challenges. If you wait and see, and don’t have a pipeline of research to address upcoming challenges, you’ll find yourself too late in the game when regulators and politicians act.

The best practice I have seen in industry and NGOs is for a significant budget to be set aside in the hands of a chief scientific advisor. The chief scientific advisor commissions studies that deal with both current and emerging challenges. This feeding of the ‘body of knowledge’ is not an add on. This constant research is core. Too few practice it.

When dealing with fisheries and chemicals I found having the best quality studies prepared ahead of time key. In both situations, that’s involved have the best experts undertake an objective analysis of the situation years ahead of when it would be officially needed. It’s obvious that the expert will use the same stringent criteria the Commission or Agencies use. There is no point using your own criteria for a study and find out it’s rejected because you are not using the Commission or Agency’s criteria.

After doing this for 20 plus years, it’s clear many years in advance when new information is going to be needed to influence decisions. Ideally, you’ll come in early, or on time, with a well-rounded body of information filling in the gaps.

If you choose to bring new research to the table just before the decision is taken, or after the decision is taken with a view to re-open the process, the current mood of most regulators is to ignore it. It’s seen as a delaying technique.

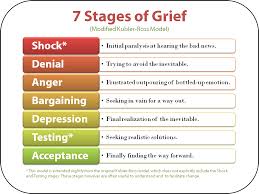

Stages of grief

Most people never really advance beyond the anger stage. It is common in industry and NGOs.

The few who do move beyond anger, tend to walk out unscathed, or relatively unscathed.

There is a phrase that indicates you will never be able to move on.

That phrase is “this is the worst thing that could ever happen”.