“Who will guard against the Guardians”. Juvenal.

Most EU legislation is delegated legislation. Around 93% (and perhaps more) of EU law adopted each year is delegated legislation. The remaining is ordinary (co-decision) legislation, where most NGOs and trade associations spend most of their time and resources, often with marginal substantive impact. Most NGOs and trade associations ignore delegated legislation because they think it is either too complicated or unimportant. I think they are wrong on both counts.

When Member States and the European Parliament hand to the European Commission, through enabling legislation, the power to bring forward new secondary laws, they are handing over considerable power. It would appear that many Member States woke up very late in the day to how much power they had handed over to the European Commission under the Lisbon Treaty (2009), and realised how little control they had to amend or block Commission delegated legislation proposals. At the time, the European Parliament only seemed to be concerned with being on the same footing as the Council, and did not seem to care that they were standing on quicksand.

Today, the Member States and the European Parliament power to control European Commission exercise of delegated power is limited.

More importantly, at the moment, given the relative secrecy in which these proposals are made and adopted, the public’s right to comment and participate is even more limited. However, important changes are happening by way of the Better Regulation reform in 2016 that will make delegated law making more open. The changes will also introduce more checks and balances on the Commission.

In this blog, I will cover in two parts, and in broad brush strokes:

- The current types of delegated legislation in the EU and 3 systems for their adoption

- How the Commission is (or is not) controlled by the European Parliament, Member States and the public

In a follow up blog, I will give some case studies that, I think, show how difficult it to stop a Commission proposal once it is made, and to update the blog in light of the new Better Regulation agreement and the Commission’s self-commitments that impact delegated legislation.

Further Reading

For those interested, I’d recommend the following further reading:

- IEEP, The New Comitology Rules: Delegated and implementing acts, May 2011

- Carl Fredrik Bergstrom’s ‘Comitology: Delegation of Powers in the European Union and the Committee System’ (2005) an excellent historical perspective and insights from some leading experts.

- Daniel Guegen, ‘Comitology: Hijacking European Power?‘ which I am prone to hand over as a present to people who are facing the labyrinth of delegated legislation. for the first time.

- Daniel Guegen and Vicky Marrissen’s Handbook on EU secondary legislation (2014)

- Daniel Guegen, who I regard as the Godfather of comitology, also publishes a comitology newsletter and provides a good training course on the system.

Introduction – Delegated Legislation in the EU

This law making procedure has been around for a long time, and it was often known by the term “comitology”, or decision making by committee. Since the Lisbon Treaty in 2009, there was an attempt to streamline and simplify the process.

The EP has provided a useful summary here.

Today, delegated legislation there are three systems for the adoption of delegated legislation. They are:

- Delegated acts

- Implementing acts, or

- Regulatory Procedure with Scrutiny.

The Lisbon Treaty only refers to delegated acts (Article 290) and implementing acts (Article 291). But, around 300 Directives exist that use the pre-2009 system and so the Regulatory Procedure with Scrutiny (RPS) system remains. The RPS is due to be phased out in 2017, but it’s end has been on the cards since 2010.

Member States and the European Parliament oversee the following types of acts/measures:

- Delegated acts: resulting from legal acts adopted after the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty (article 290);

- Implementing acts: resulting from legal acts adopted after the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty (Article 291)

- Measures falling under the Regulatory Procedure with Scrutiny (RPS): resulting from legislative acts adopted before the entry into force of the Treaty, but which are not yet aligned.

In this blog I focus on the Parliament as they have, to date, been the most active branch of the legislature, in challenging the use (or abuse) of delegated power.

Not Avoiding Political Choices

First, it is important to realise that the Parliament and Council are making a political choice when the decide or not to delegate rule making powers to the Commission. It comes down to whether the, in particular for the Parliament, whether they have a future say in any future specific measure (delegated acts) or not (implementing measure).

Second, much to the surprise of many in Brussels, there are core limits to what can be delegated. The Parliament and Council can not delegate “essential elements”. This means if the measure concerns an essential emolument it can only be dealt with in the ordinary legislation and that power to introduce measures can not be delegated.

The Court of Justice has given their opinion on what an “essential element” means. In the German Sheep meat case the Court rules that : “rules which (…) are essential to the subject-matter envisaged” and “which are intended to give concrete shape to the fundamental guidelines of Community policy.” “[R]ules being merely of an implementing nature may be delegated to the Commission” (Judgment of 27 October 1992, C-240/90, Germany v Commission, paragraphs 36 and 37).

The Court developed their thinking and clarified that essential elements of a basic are those that “entail political choices falling within the responsibilities of the European Union legislature, [by requiring] the conflicting interests at issue to be weighed up on the basis of a number of assessments”(Judgment of 5 September 2012, Case C-355/10, European Parliament v. Council, paragraphs 63, 76 to 78).

This is important because this prevents the EU legislature avoiding taking hard policy choices. They Parliament and Council can not avoid taking political choices by asking the Commission to settle them for them via delegated legislation. This is in marked contrast to the US, where, at least in the field of air quality regulation, the Congress finds itself unable to make tough political choices of what air pollutant limits should be, and delegates to the US EPA those choices. Fortunately, in Europe, we avoid that abdication of political responsibility.

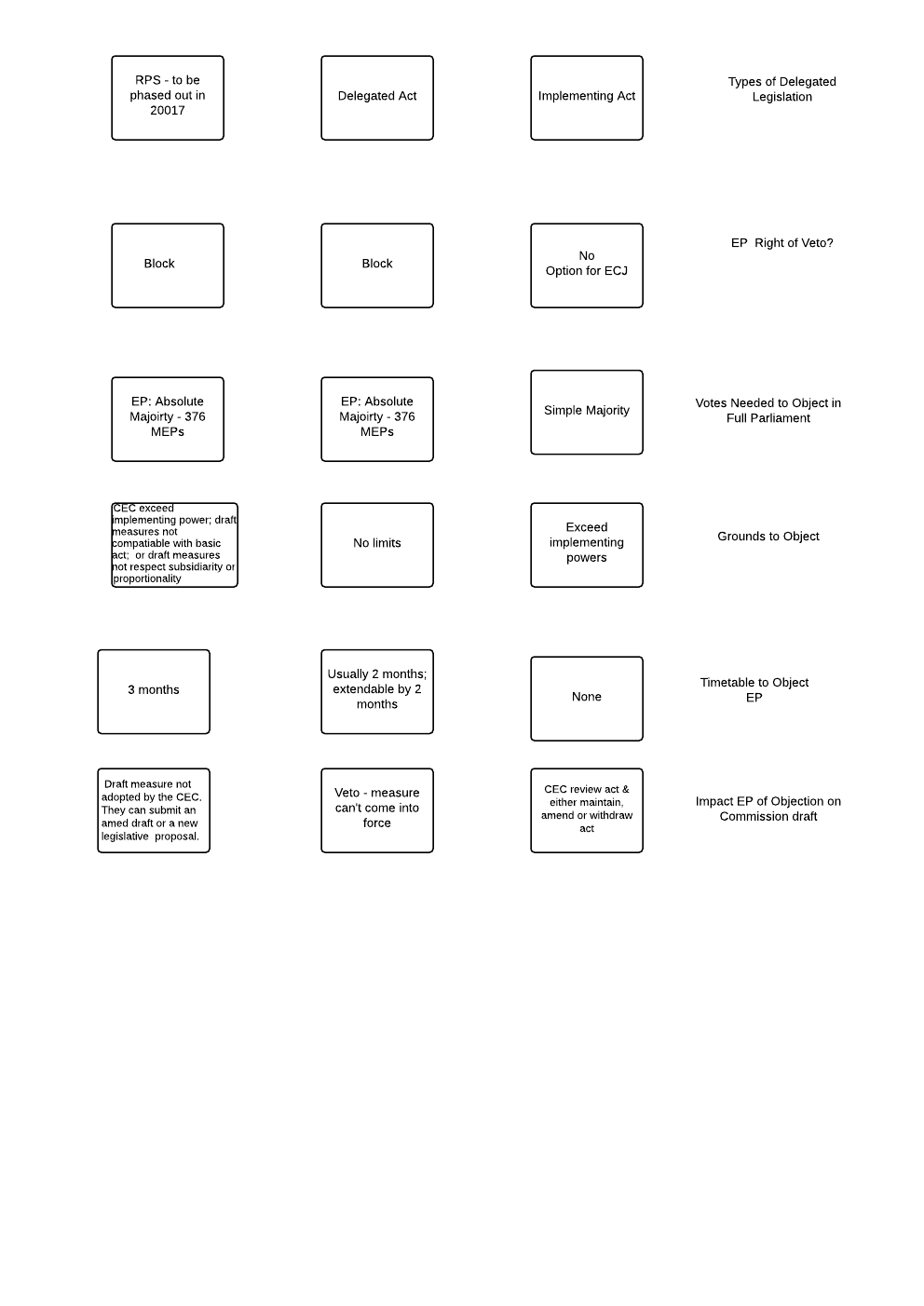

A summary of the grounds to object, timing, majorities in the EP and consequences of objection is below.

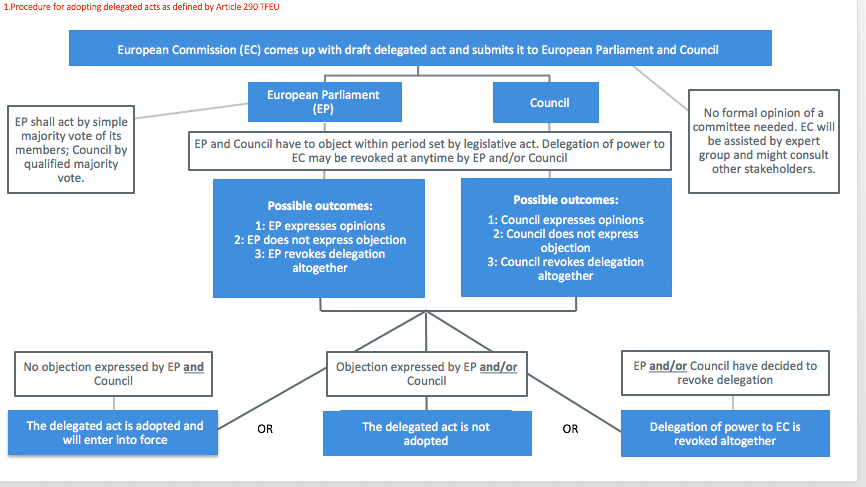

- Article 290 – Delegated Acts

As the EP state “Delegated acts are used to change or supplement existing legislation. They are a way for Parliament and the Council to authorise the European Commission to revise non-essential parts of legislation, for example by adding an annex. However, Parliament and Council cannot delegate their legislative powers to the Commission to change essential parts of legislative acts.

If Parliament and the Council do not agree with the Commission’s subsequent proposal, they can veto it.”

The Parliament usually have 2 months with the possibility to ask for an extension of another 2 months. For environment measures, the Environment Committee send a monthly newsletter for both draft delegated, RPS, and implementing acts. A MEP needs to email the Environment Committee Chair and Secretariat of the intention to object. If the Committee backs the objection (by simple majority) the matter is usually tabled for a vote at the next plenary session of the Parliament. At the plenary, the high hurdle of 376, an absolute majority, is set to block a draft measure.

An example of a successful challenge to a proposed delegated act is the European Parliament’s successful challenge is on 12 March 2014 to the Commission’s proposed measure on the definition of engineered nano materials in food (see here). The Parliament’s challenge was adopted 402 votes for, 258 against and 14 abstentions.The Commission’s proposal was defeated.

Article 290

1. A legislative act may delegate to the Commission the power to adopt non-legislative acts of general application to supplement or amend certain non-essential elements of the legislative act.

The objectives, content, scope and duration of the delegation of power shall be explicitly defined in the legislative acts. The essential elements of an area shall be reserved for the legislative act and accordingly shall not be the subject of a delegation of power.

2. Legislative acts shall explicitly lay down the conditions to which the delegation is subject; these conditions may be as follows:

|

(a) |

the European Parliament or the Council may decide to revoke the delegation; |

|

(b) |

the delegated act may enter into force only if no objection has been expressed by the European Parliament or the Council within a period set by the legislative act. |

For the purposes of (a) and (b), the European Parliament shall act by a majority of its component members, and the Council by a qualified majority.

3. The adjective ‘delegated’ shall be inserted in the title of delegated acts.

2. Article 291 – Implementing Acts

As the EP write “Implementing acts describe how legislative acts should be implemented. They are normally prepared by the Commission, which consults committees made up of representatives from EU countries.

MEPs can object to an implementing act. Although the Commission must then consider Parliament’s position, it is not bound by it.”.

Article 291

1. Member States shall adopt all measures of national law necessary to implement legally binding Union acts.

2. Where uniform conditions for implementing legally binding Union acts are needed, those acts shall confer implementing powers on the Commission, or, in duly justified specific cases and in the cases provided for in Articles 24 and 26 of the Treaty on European Union, on the Council.

3. For the purposes of paragraph 2, the European Parliament and the Council, acting by means of regulations in accordance with the ordinary legislative procedure, shall lay down in advance the rules and general principles concerning mechanisms for control by Member States of the Commission’s exercise of implementing powers.

4. The word ‘implementing’ shall be inserted in the title of implementing acts.

An example of a challenge to an implementing act is Authorisation of GM maize 1507 for cultivation (see here). The vote on 16 January 2014 was carried with 385 in favour, 201 against, and 30 abstentions. The Commission ignored the European Parliament.

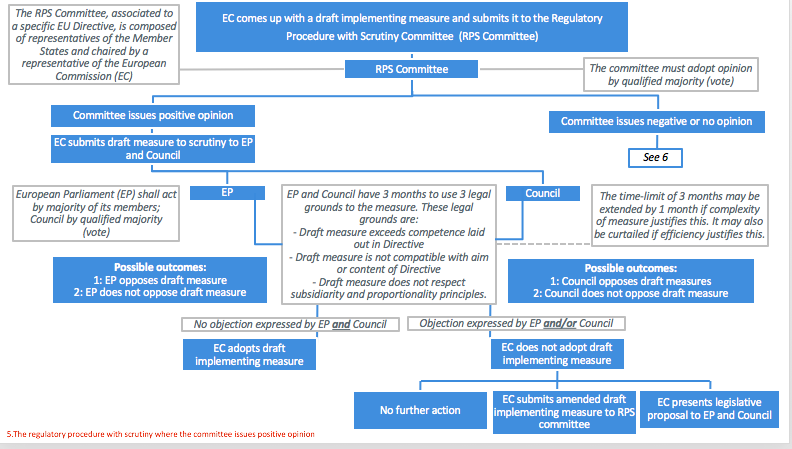

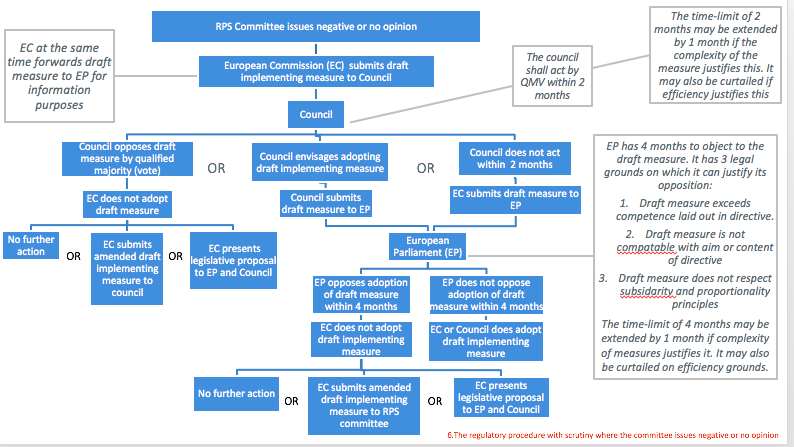

3. Regulatory Procedure with Scrutiny

The EP state “This is a defunct comitology procedure that operated between 2006 and 2009 for “quasi-legislative measures. It can no longer be used in new legislation but appears in more than 300 existing legal acts and will temporarily continue to apply in these acts until they are formally amended. This procedure empowers the European Parliament and EU Council to block a measure proposed by the Commission if it:

- exceeds the Commission’s implementing powers,

- is not compatible with the aim or content of the legal act, or

- exceeds the EU’s powers or remit (see subsidiarity

and proportionality

and proportionality  ).”

).”

RPS is used extensively in the environment field. Around 300 directives use the procedure. The Commission is due to table a omnibus proposal to update all the RPS into delegated acts for 2006. That said, talk about the demise of RPS has been on the table since 2010.

An example of a successful challenge to a RPS measure is Parliament’s challenge to criteria for End-of-waste of paper waste (see here). This vote on 4 th December 2012 was adopted with 606 for, 77 against and 10 abstentions.

How often used

It is estimated that around 93% of EU laws adopted each year are delegated legislation.

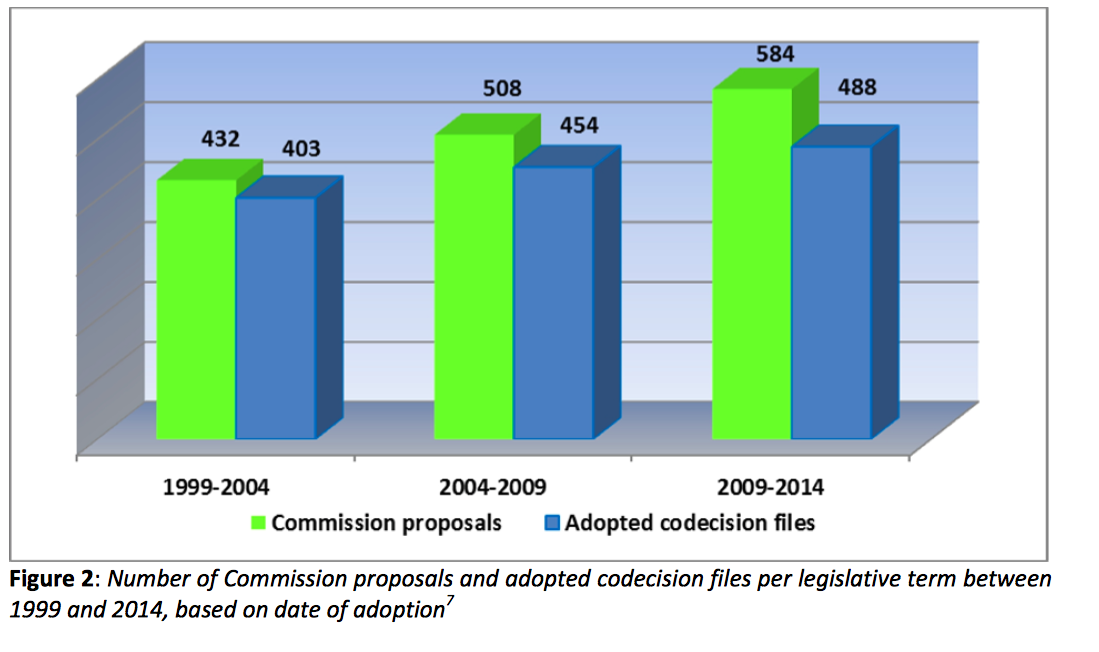

In the last European Parliament, the 7th legislative term (14 July 2009 to 30 June 2014), the European Commission tabled 584 co-decision/ordinary legislative proposals, and 488 files were adopted by the co-legilsators (the European Parliament and Council).

Over time, the trend for more co-decision proposals has grown. See below: (Source: Activity Report on Codecision and Conciliation, page.4.)

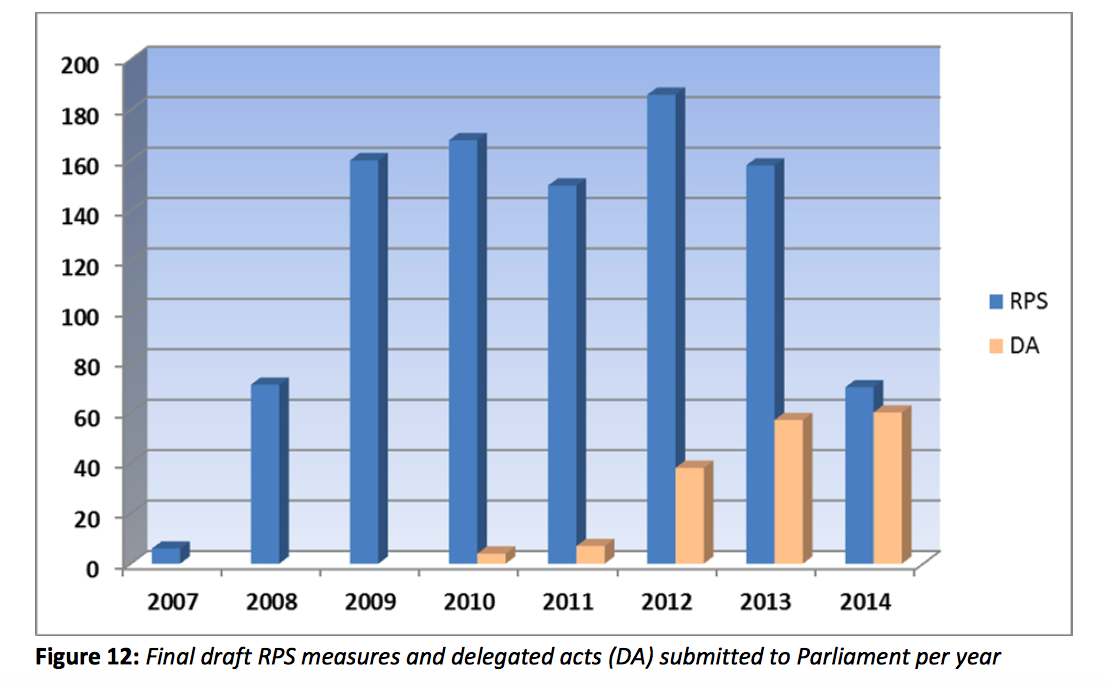

But, the adoption of proposed delegated legislation is far higher. The same Parliament report provides the following chart (page 24) on the growing volume of delegated legislation that has been sent to the Parliament.

93% (or even 97%) of EU law passed each year

The European Commission in their “Report on the Working of the Committees during 2014” note that 1 899 Opinions were adopted, 1 563 Implementing Acts were adopted, and 165 RPS measures were adopted (see page 7).

By that measure, the ordinary (co-decision) legislation represents around 3% of the overall legislative workload of the EU.

More Examples of Delegated Legislation

Today, delegated legislation is either an delegated act or an implementing act. It will be clear from the legal text.

The European Parliament have provided three recent examples where the European Parliament sought to control Commission delegated legislative proposals:

“MEPs vetoed a delegated act concerning suger in baby food in January, as they fear the allowed limits are too high.

In February MEPs decided against vetoing a delegated act proposing to temporarily raise NOx emission limits for diesel cars after the Commission promised to include a review clause.

Also in February MEPs objected to implementing acts approving three types of genetically modified soybeans as they were concerned the soybeans could contain traces of a herbicide that was classified as “probably carcinogenic”.

The main consequence is that the Parliament or Council (or both) will find it far easier to veto a delegated act. The Commission has not withdrawn any implementing act measure the Parliament has objected to.

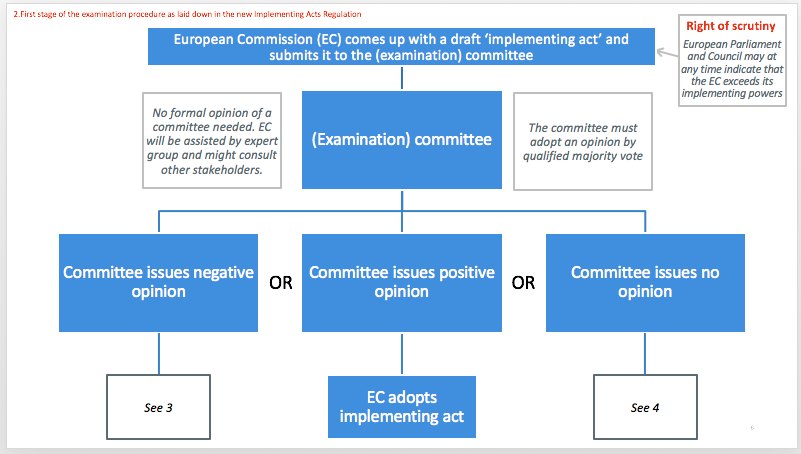

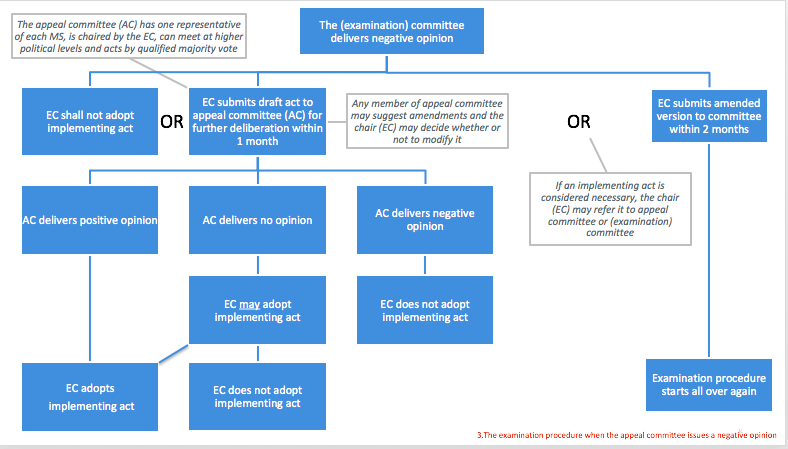

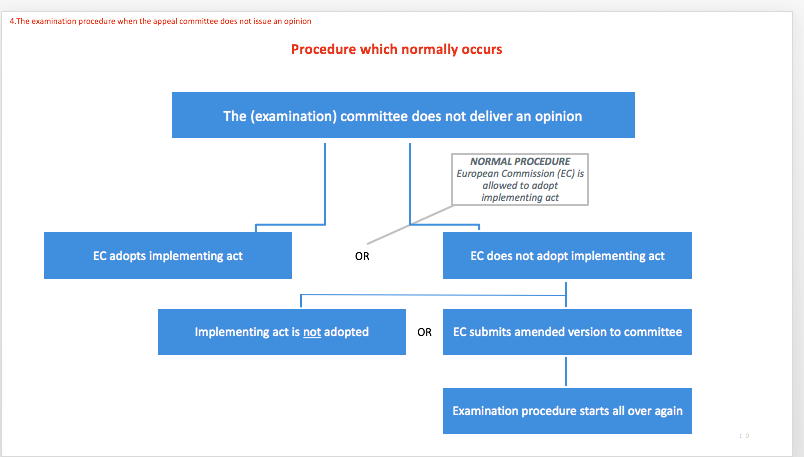

The Process in Charts

The IEEP have produced an excellent guide on the existing system which you can find here. The charts below are derived from that study and provide a useful schematic of the current system. These charts are helpful high level maps of the pathway to travel, but they are not detailed travel plans, which are individual for each journey.

- Delegated Acts

2. Implementing Acts

3. Regulatory Procedure with Scrutiny

The Financial Service legislation use a slightly different system under the Lamfalussy system.

Tracking the Proposals

Public

For the public, there is no public source of draft measures prepared by the Commission that the public can examine. Unlike ordinary legislation, where you can look up proposals and where they are via EUR-lex there is no similar database for delegated legislation.

You can embark on a journey of discovery and search the Commission’s comitology database for proposed implementing acts and RPS measures. But, so poor is it’s ease of use that asking a friendly experienced cyber hacker would be advisable. And, if the Commission forget to transfer the documents to the Parliament, you’ll still be none the wiser as to what proposals are lurking around.

Fortunately, the EFTA States in February 2016 launched their own database of EU delegated legislative proposals. As the EFTA agreement does not cover all areas, such as fisheries, it covers most, but not all, proposals. It is a very clear database.

European Parliament and Council

Today the Commission notify the Member States and the European Parliament of their proposals via a functional email box, or for implementing acts, via a database.

The functional email box has limitations. Whilst many of the measures are technical, some are sensitive, and sometimes the Commission Services have shown themselves unable to operate the system. The system operates on a basis of trust with the Commission sending the correct files to the Council and the Parliament by way of functional email boxes. Sometimes the Commission have not done this.

For example, as recently as December 2014, the Environment Committee started an objection to a “delegated act entitled Commission delegated Regulation (EU) No …/..of of 12.12.2013 amending Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the provision of food information to consumers as regards the definition of ‘engineered nanomaterials’. The delegated Regulation adapts the existing definition of ‘engineered nanomaterials’ in Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 to Recommendation 2011/696/EU on the definition of nanomaterial adopted by the Commission on 18 October 2011.”

The objection from the Parliament centred on (1) substantive and (2) procedural grounds. In this case, the European Commission published the act before the period of objection from the Parliament or Council had expired. The Commission acknowledged their error, citing a clerical error and a high volumes of procedures. So, whilst the act was published on 19 December 2014, the error was spotted, and a notice published in the Official Journal that the notice of 19 December was null and void. The Parliament were notified on 19 December of the error.

This case is not isolated. In 2000, the Environment Committee stumbled upon the systematic non-transmission of proposals from the Commission to the European Parliament for many proposals across a few Commission departments.

Today, this does not mean the draft measures do not leak. Well sourced interests will gain access to the documents, but the public won’t. The European Parliament in practice is left to being informed by well informed “observers” about “problematic proposals” coming down the pipeline.

Impact Assessments

Delegated legislation that has a “serious impact” is meant to have an impact assessment. This is a good way members of the public to see what proposals are in the pipeline.

Measures that have a significant impact are already meant to have an accompanying road map. However, it is interesting to observe that even today many delegated legislative proposals the Commission put forward, that have significant first order, let alone second or third order impacts, still have no Road Maps. Without the Commission Services policing themselves to flag significant impacts with their own proposals, it is unlikely that politically or economically sensitive proposals will be weeded out or flagged for political sign before adoption. And, as nearly 99% of EU delegated or implementing acts go through untouched by the influence of the Parliament or Member Stares, the only way to weed out weak proposals is the inter-service consultation phase. I’ll touch on that in tomorrow’s blog.

Follow Up

Tomorrow, I will look at some case studies to show how difficult it is for the Parliament and Council to challenge the Commission. In fact, I’d go so far that this power of control over the Commission verges on to hypothetical. For example, the Commission have never withdrawn an implementing act challenged by the Parliament.

Second, I’ll detail how the new Better Regulation Agreement changes the mechanics of the current system (which it does for delegated acts) and how the Commission’s unilateral commitments on Better Regulation and delegated legislation (public consultation on draft measures) will positively impact open law making.

Thank you